Regenerative Tourism or Sustainable Tourism?

- Feb 1, 2021

- 13 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2025

Why does knowing the difference between regenerative and sustainable tourism matter?

There are many questions about the difference between regenerative and sustainable tourism. Some argue that regenerative tourism as a new word and a way of diffusing attention away from sustainable tourism. Some see it as just another buzzword and dismiss without another thought. Some align regenerative tourism with a market segment and see it as re-generating travellers through health and wellness visitor experiences.

Regenerative tourism is so much more. Understanding the meaning and distinguishing features of each term are important. They are complementary, not competitive terms, but and are based on vastly different mental models of tourism. They are not interchangeable. It starts with understanding how the concept of sustainability has evolved and the problem with the mental model and the mindset that has evolved and shaped how sustainability is framed.

Origins: Sustainable Development and Limits to Growth

Inspired by the Brundtland Report Our Common Future when it was first published in 1987 and working in sustainability for 25+ years, a holistic approach to sustainability was my unquestioned starting point. The Chairperson of the World Commission of the Environment and Development, Gro Harlem Brundtland, described a 'head-heart-gut' concept of sustainability in Our Common Future. The environment, she wrote, "is where we all live; and "development" is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode".

Even before we started talking about 'sustainable development' and 'planetary boundaries', there was 'Limits to Acceptable Change (LACs)' and 'Ultimate Environmental Thresholds' (UETs). In other words, the idea that we have finite limits to the use of natural resources - that we cannot take more than we replenish - has always been a kind of starting point. This idea is one of the core principles of living systems - that a healthy system reinvests in itself, healing, repairing and regenerating. The concept is sound, but the terminology, the politics and the and language games is where

Sustainability is Dialogic

Terms like sustainability are dialogic. That is, the context and the words employed around the core term shape both meaning and action. For example, companies can talk about a sustainable financial model or completing a sustainability certification all while continuing to extract more than they reinvest back into the system. Governments can talk about sustainable development while simultaneously their economists fixate on growth, investment returns and stock market performance. Researchers trained within the scientific paradigm tend to see sustainability as a concept out there that can be defined, measured, and achieved. The tourism sector talks about sustainability as way of being a good corporate citizen and secure a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Note that Indigenous peoples don't use the term sustainability - because its a scientific word that is derived from a scientific mindset, mental model, and worldview. Indigenous knowledge systems draw from more diverse knowledge systems and sources of information. But more about this later...

Hidden Assumptions and Mental Models

You see where I am going with this argument? The consequence of this word salad and the language games is that words like 'sustainable' and 'sustainability' take on meanings within the context. They are operationalised in a way that supports the dominant political and institutional interests in that context. What makes matters worse is that we give very little attention to pausing, reflecting and questioning on where our assumptions and mental models have come from. Knowledge is assumed to be linear and cumulative, so we rarely stop to invite new ideas, sources of information and ways of seeing. Questioning our mental models and assumptions can be so challenging - so discombobulating - that it's safer to push back, not engage, ignore or gaslight perspectives that challenge our worldview.

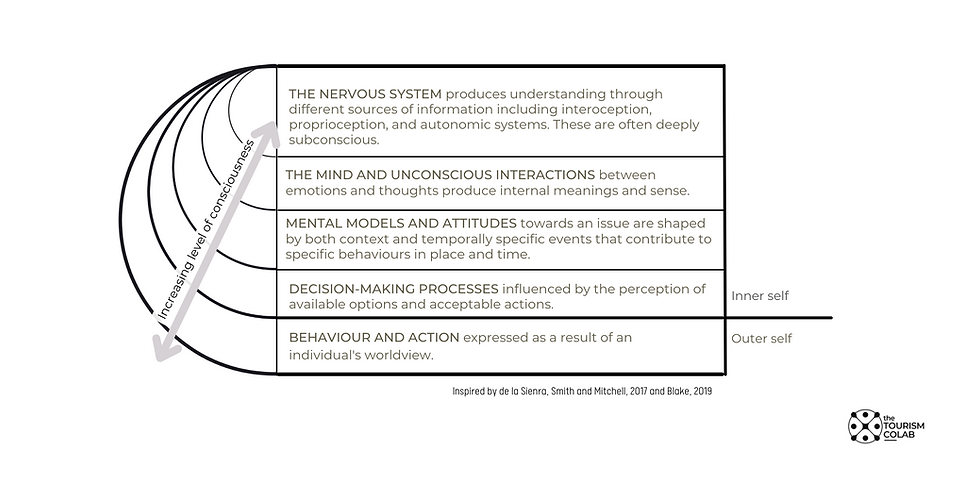

As the diagram below illustrates, we spend most of our time in the 'outer world' - our behaviours and actions. We might sometimes explicitly consider our decision-making processes, but few spend any time delving into our inner core to better understand our mental models (i.e. how the world works), making our unconscious conscious or to truly build awareness of our nervous systems and the knowledge it carries. It's only when we trying develop these deeper level of conscious awareness that we become privy to the implicit assumptions that shape our thinking and actions and behaviour

Word Salad and Greenwashing

Ancillary words like 'growth', 'innovation' and 'development' shape and co-opt the interpretation of the term 'sustainable' in (sub)conscious ways. For example, 'green growth' is a good example of this language game - it works on our psychology to suggest that we can continue to grow and take more resources than we regenerate - but calling it 'green growth' helps to remove the guilt but doesn't change the business as usual extractive assumptions we carry about growth.

The agenda of institutions, and the context in which they use the term 'sustainability' have shaped how you might think about its meaning. These political agendas and language games have served to muddy the concept. So too have the silos and knowledge bubbles we work within. As a result, there is no single definitive meaning of the term sustainability - despite best intentions.

No wonder greenwashing is a rising threat. But it's not just nefarious business interests that are the problem. The problem is rooted in overuse of the words and combinations of words in various contexts. It's rooted in the dominance (and even indoctrination) of the rational scientific paradigm, and its fixation with certainty, rules, frameworks, metrics and measurement. It's rooted in our discomfort with uncertainty and the need for fixed answers, performance and metrics.

How Sustainable Development was Co-opted into Business as Usual

Brundtland's version of sustainability was a call to take personal responsibility: to 'think globally, but act locally'. The survival of humans and nature was seen as a complex, wicked problem with many moving parts. No single entity had control or the overarching solutions. It required action by many, all working together and an eye on the direction of change. In other words, it was everyone's problem but no one's responsibility. Improvement required working collaboratively and in awareness of the complex, multiscalar, multi-actor challenges. The Brundtland Report was a clarion call to move from the individualism and self-interest of the competitive, mechanistic paradigm to a collective approach.

Not knowing any other way to address the challenge, international organisations channelled scientific approaches to problem-solving. They began to break down the complexity of the challenge into smaller, individual, bite-sized parts. Brightly coloured tiles were born, and, visually, they captured a powerful message. This reductionist approach meant that the complex relationships between individual actions were not understood. While action in one area was celebrated, a range of unintended consequences went unnoticed somewhere else in the system.

Soon, the challenge of addressing sustainable development through a business lens quickly took front and centre stage.

Rational scientific thinking, dominated by cognitive (head-brain) knowledge, was the dominant paradigm at the time. This was before the culture wars (i.e. the fight for legitimacy between rational science and subjective, qualitative knowledge). It was before a time when other kinds of embodied, cultural, and relational knowledge were considered legitimate and worthy. Put simply, sustainability became a rational technical problem to be solved with rational technical solutions.

Neoliberal values also came into play in the 1980s. The idea that sustainability could be addressed by markets became the dominant approach. Governments could outsource the problem and their international commitments by finding commercial solutions. In the process, they could distance themselves from taking real, personal responsibility. Applying performance metrics to not-for-profits, aid agencies and commercial delivery partners, governments could still report on progress at the same time they pursued business-as-usual objectives. The "me" agenda flourished while the collective "we" action that Brundtland had envisaged failed to gain traction.

Herein lies the conundrum. As a rational scientific, technical solution, the SDGs have failed to address the much-needed mindset shift that Our Common Future originally identified.

The SDGs consolidating

Over the intervening decades, sustainability has morphed into a core plank for international aid, consulting businesses and the 'expert' sector. Put simply, it has become an enormous business opportunity. But unintended consequences fall between the cracks.

The business of environmental expertise has boomed, which has, in turn, contributed to unsustainable behaviour and practices. Sustainability has propelled the growth of consulting companies, commercialised intellectual products, and platforms. It's seen the rise of global thought leaders travelling the planet to sell the message. The commercialisation of sustainable development was recognised during the MDG phase along with several other challenges, including the unintended consequences emerging from a focus on one or a few SDGs and the outsourcing and distancing of responsibility (Fehling et al., 2013).

On the positive side, the SDGs have shone a light on the enormity of the global challenge, and there have been important intellectual gains and innovations from private sector involvement. Empowering a collective global narrative has also been an important contribution.

But progress is slow. Too slow. Catalyst 2030 in their social progress report Getting from crisis to systems change: Advice for leaders in the time of COVID estimates that it will be 2073 before the SDGs are realised. Mindset, culture and business-dominant values are standing in the way of progress.

[Update 2024: The UN's own progress report shows that only 17& of the 1967 tarets are on track to be met with another 67% making mild or limited progress]

Times are changing

But times change. Perceptions shift. The rational technical mindset and the neoliberal value systems of the 1980s are now being questioned in light of advances in how we perceive, frame, interpret and address complex, wicked problems. We have come to accept there are other ways of knowing. Neuroscience confirms something Indigenous cultures have always known - that intelligence derived from the heart and gut (instinct) are equally important in understanding. Put simply, the rational scientific paradigm has placed barriers around our thinking; it has stopped us from thinking, feeling and acting with the collective intelligence of heat, heart and gut.

Of course, technical solutions still have a role to play, but these solutions have not addressed some of the more challenging human dimensions of the sustainability challenge.

Put simply, the greatest challenge we face is to evolve the way that we think, value and relate to the world around us. Our greatest challenge is to see and frame the problem of sustainability as if our very own lives, that of future generations, the planet, and its incredible biodiversity, are dependent upon our own personal actions. Not only should we move beyond 'do no harm', we should give back and contribute to the regeneration of communities and nature. It requires that we revisit what we deeply value and what we care about.

Regeneration, or regenerative tourism in our case, is the mindset change and the paradigm shift that accelerates the pursuit of sustainable tourism and the SDGs.

Seven Points of Departure

The wonderful thing about Regenerative Tourism is that it brings together and creates a narrative arc that threads together the shifts in thinking in tourism and, more broadly, in how we think of terms like development, progress, growth and flourishing. It took a wonderful storyteller in Anna Pollock to thread these elements together. Some of these lines of thinking have threaded themselves, like DNA, through my own community project work for over 25 years, and now they are coming together like a jigsaw puzzle. Once you see it, you cannot unsee it! In regenerative tourism, the task it to help others see it and evolve the thinking beyond, but not abandoning, the SGDs.

Seven key points of departure for regenerative tourism are outlined. This short list aims to help distinguish regenerative tourism from sustainable tourism. If you spot additional points of departure, don't worry—there will be a follow-up post!

1. Sustainable tourism is good, but not enough.

The range of challenges we currently face at a global level, including the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, ecosystem decline, the restructuring of work, accumulation of wealth and rising inequality, inclusion, access to education, and the health crisis, illustrate that the SDGs, while important, are simply not enough. The problem with the SDGs and associated metrics is the unintended consequence of mediocrity. It’s captured in Goodhart’s Law (1975) “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to become a good measure’. In other words, when a target is set and it becomes a goal, people will target that goal regardless of the consequences. They will pursue that 'tick of approval' at the risk of ignoring the flow-on effects and impacts that are experienced elsewhere in the system.

2. Transactional ethics of doing less harm versus an ethic of care.

Most of us don't think about our ethical position at all. It's taken for granted and unquestioned. The scientific revolution gave us a worldview where the white European man (and yes, it was gender-specific!) was centre stage, and rational scientific thinking was superior. The role of nature was to service his needs, which were to power the economy, extract resources and accumulate wealth. The responsibility to care for nature was framed as 'resource management', where nature's resources needed to be managed to feed economic growth. Scientific management ensured resources were carved up into components - water, soil, forests, air, fisheries, and so on - and managed in machine bureaucracies where departments rarely interacted (Dredge and Jenkins 2007). This organisation reinforced the separation of Humans and Nature. The SDGs are an extension of this approach and are developed from a scientific mindset. They reinforce the separation of humans and nature. The SDGs become targets and the race to achieve these targets - an ecolabel or certificate standard - distances humans from the real existential challenge we face.

Regenerative principles are founded on holistic management approaches, mutual respect, networked relations, and connection with nature and all living and non-living things. Regenerative tourism is not guided by metrics but by a deeper ethical position not only to do no harm but to give back more than we take, i.e. to regenerate.

3. Scientific thinking versus knowing with Nature.

The scientific paradigm, which has dominated since the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution starting in the 18th century, is being challenged. Not only are different worldviews emerging, but interest in indigenous ways of knowing and working with nature is challenging the traditional white Western worldviews. Indigenous knowledge connects diverse areas of knowledge and practice, such as ecology, astronomy, climate, culture, law and spirituality, and seeks harmony and balance with nature. Distance and domination over nature are to be avoided.

Regenerative tourism challenges the current view of the tourism system, which is traditionally conceptualised as an industrial system made up of parts that need to be managed according to the rules of scientific management. It calls for a rebalancing and a need to place more emphasis on the intentional design of tourism and visitor economies to balance the needs of people and communities with the regeneration and resilience-building with and for nature

4. Economic value versus holistic value co-creation.

For decades, the assumption underpinning tourism has been that it should be industry—or investment-facing[3]. In that framing, all other stakeholders who contribute social, cultural, and natural value, for instance, or have to deal with the loss of value, were sidelined in this narrow worldview. Government policy and destination management have focused almost exclusively on economic value and attracting economic investment to the detriment of a wider and more holistic understanding of the value of 'investment' and 'money'.

Tourism generates positive value (benefits) and negative value (impacts or costs). This value can be tangible or intangible. We currently have no real understanding of the value created by tourism, where that value is accumulated, and what value is destroyed in the process of 'doing tourism'. A mapping of the true value of tourism (both positive and negative) is needed. The concept of investment needs to be widened to other kinds of investment (shouldn't we also be investing in environmental value, social value, cultural value and so on). Adopting multi-stakeholder facing approaches that ensure those stakeholders who invest in tourism (including Nature) should be supported would appear to support regenerative tourism.

5. Outside experts versus local knowledge and capacity building.

For too long, we have placed emphasis on outside experts coming in and telling local communities what to do. They spend too little time understanding the challenges and how issues are experienced and appreciating the ingenuity of the local community. Template plans might simplify and scale a standard approach, but this ignores the very essence and character of the visitor economy, the unique energy and capacity of local people and business communities. These local 'assets' are the key to the future and the source of uniqueness for businesses, destinations and communities. Harnessing the knowledge, insights, creative problem-solving and ownership of local stakeholders builds local capacity, achieves stronger ownership, and leads to more resilient and engaged communities.

6. Strategic versus regenerative leadership.

Scientific management has given us all manner of leadership theories. While we can scientific principles in leadership, our research [4] and our lived experience show that leadership depends on:

(a) the capacity of the individual to lead;

(b) the freedom afforded by the organisation to lead; and

(c) the social context, interactions and cultural milieu.

Scientific styles of leadership rely on leaders and followers, metrics, command and control structures, and clear role definitions. To achieve regenerative tourism in an age of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, we require an ethos, a mindset, and a range of intangible qualities that are difficult to formularise. Now more than ever, adaptive, resilient, inspiring, intergenerational and values-based leadership is required in tourism. The industrial tourism operating system may need an overhaul to allow the evolution of new regenerative leadership.

7. Management versus designing in positive contributions.

Intentional design, as the term suggests, involves the intentional and inclusive design of complex dynamic systems. It listens and responds to all stakeholders and their challenges (living and non-living), always aware of the interconnections and influences at other scales. It is, by default, the polar opposite of strategic management, which is based on hard rules and procedures. Intentional design involves deep understanding, listening and building empathy, and taking responsibility to do no harm, to respect Nature, to lean in and co-create a future that replenishes and enhances our capacity to flourish on this planet. Intentional design of our economy, or our environment and our communities, is the key to resilience {6}.

Tourism is place-based yet the place-based design of our visitor economies is generally not a task for Destination Management Organisations (DMOs). Urban and environmental planners undertake this role, often with other objectives in mind. Tourism relies on the special and unique qualities of local places - environments, communities and individuals - all working together to showcase, welcome, and care for the visitors. The intentional design approach seeks to enhance the functionality, connectivity, resilience and flourishing of these places across different sectors, silos and spheres.

References

Fehling, M. Nelson, B.D. & Venkatapuram, S. (2013) Limitations of the Millennium Development Goals: a literature review, Global Public Health, 8:10, 1109-1122, DOI: 10.1080/17441692.2013.845676

Goodhart, C. 1975. Problems of Monetary Management: The U.K. Experience. Papers in Monetary Economics. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia.

Dredge, D. & Jenkins, J. 2007. Tourism Policy and Planning. Brisbane, Wiley & Sons.

Phi, G. & Dredge, D. 2020. Critical issues in tourism co-creation. Journal of Recreation Research, 44: 281.

Dredge, D. & Schott, C. 2012. Academic agency and leadership in tourism. Journal of Teaching in Travel and Tourism.

Höckert. E. et al., 2020. Knowing with Nature. The future of tourism education in the Anthropocene. Journal of teaching in Travel and Tourism, 20: 169

Cave, J. & Dredge, D. 2020. Reworking Tourism: Diverse Economies in a changing world. Routledge.

About The Tourism CoLab

THE TOURISM COLAB is a global hub for creative thinking, capacity building, leadership, experimentation and change-making. Our mission is to deliver cutting-edge, innovative learning experiences, workshops and capacity-building journeys in travel, tourism, and visitor economies. We help to grow sustainable tourism and visitor economies that deliver net benefits to people, nature and local communities. We're passionate about the power of creative, playful design-led approaches, holding space for community and co-designing innovative solutions to complex challenges. That's why we have gained a reputation as a global innovation lighthouse for regenerative, inclusive and purpose-led tourism and visitor economies. Join us!